- Home

- Alex McGlothlin

The Medium of Desire Page 15

The Medium of Desire Read online

Page 15

Olivia changed into an open-back, silk, bandana shirt with a forest green print. She was talking to one of his good friends, a landscape architect named Shogon, who Brett often leaned on when he needed insight into his landscapes. Shogon was a large, healthy black guy with bulgy muscles. His jealousy grew as Shogon and Oliva talked, but the rational man in him believed nothing was there; the sensualist even relished the jealousy. Perversely, it felt good to care this much, an offshoot of that critical energy that infused everything. If he was alone, he could definitely use this to whip up some paintings. But seeing all these friends at his place on the spur of the moment made him feel good.

Olivia’s conversation with Shogon broke up, and she started looking around. What did she want? A beer? Cigarette? Next conversation? He knew when her eyes locked on him.

“I like the way you live,” she said, wrapping an arm around his neck, pushing her lips against his.

Chapter 26

Olivia had persuaded Brett to take her to a concert series she had read about in Style Weekly called “Friday’s at Five.” A different band played every Friday on a little island in the James River, with food vendors, wine and beer tents. It was the kind of place a 21st Century, 25-year old Huckleberry Finn would be drawn to. She loved Brett’s passion for painting, but he was a maniac when it came to the length of his sessions, painting in a fury for hours. He was producing awesome work, and she took no issue with his drive, but his mania didn’t always make for the best company. Even if she was in the presence of greatness, and she did think he was great, she still wanted, no needed, a fair amount of companionship.

They biked downtown, farther than she thought they needed to go to get to Brown’s Island, but they careened down a vacant Cary Street, gliding downhill until they hit the downtown traffic. All the skyscrapers reminded her of New York, Richmond’s financial playground, filled with glass, cement and steel colossuses. Business suits flooded the streets. Deals were being done outside, on the first floor, in the penthouse, in the elevator, on the phone, over secure email, by FedEx and personal courier, networked through so-and-so’s cousin or old college roommate. Business days ended but deals never slept. Once a second person was assigned to a project, the deal took on a life of its own, sucking in increasingly more people and resources, tethering them to an idea, a blueprint outlined in term sheets and binding legal agreements, before the money spigot turned on, money wired from here to there, mobilizing more people into action—a new skyscraper erected, an idle office building put into full commission as a newly hired staff hauled in boxes of personal effects, PowerPoints illuminating screens that birthed new deals. Deal flow was a never-ending cycle. Fighting over deals never ended, everyone scrambling for the business everyone else wanted.

They merged onto 11th Street, passed the Tobacco Company’s warehouse façade, under an overpass and down to the canal, where, dismounted, they chained up their bikes. They walked along the canal, passing through a turn-of-the-century industrial ruin, the ceiling blown out, the walls covered in giant murals: human manikins breaking the three-dimensional plane, variously arranged around a bullseye; the face of an owl with roots growing out of its eyebrows; a busty maid sketched in lead and pink with a scroll wrapped about that read “James is that you I smell;” a mural of a pastoral city situated along a river underneath the watchful gaze of a rainbow.

A set of businesspersons merged with them from a set of steps that connected the canal walk to two looming skyscrapers tagged with the expensive names of the exalted patrons of their profession.

“Do we need tickets?” one of the men asked.

“You never need tickets to this thing.”

“I tried to go last week and it was sold out.”

“Must have been the most crowded ever,” the other said.

“Put your phone away.”

“I’ve got to get this email out.”

One of the guys swiped at his colleague’s cell phone, but the guy jerked his phone away just in time.

They reminded her of warriors fresh off the battlefield. She missed that feeling, that moment of release after a high-stress day at the office. They, her people, were a far cry from Brett’s friends she had met last night. Brett’s friends were interesting, terrifically interesting people, but what different, uncertain lives they led. How were artistic types so comfortable when they lived without income security, health insurance, prospects of upward mobility? Artists must share a secret no one had bothered to share with her.

Brett paid a few dollars at the island’s entrance, and they joined the throngs of Friday revelers already assembled.

“There’s Cal.” Brett pointed, taking Olivia by the hand and guiding her through the crowd, close to a beer truck. Brett and Cal hugged it out, and Brett introduced the two.

“I’m going to grab us a couple of beers. You watch her for me?” Brett asked.

Cal nodded.

“So what’s your story, Cal?” Olivia asked.

“What do you want to know?”

“What do you do?”

“I’m a sculptor. How about you?”

“Nothing, at the moment.”

“You must be one of those artists of life Brett’s always speculating about.”

“That’s a flattering description. What’s an artist of life?”

“You know, that whole, you don’t have to be engaged in production to validate your self-worth type. Like, business people don’t appreciate life because they’re so busy hoarding cash they don’t even stop to consider why or appreciate the beauty and awe of it all. Then there’s the artists, we stop to appreciate the beauty, but we sacrifice so much time trying to preserve a record, it’s like, why bother with any of it? Why not just enjoy the here and now and realize everything we build with our hands is eventually going to decay and be forgotten.”

“So what keeps you sculpting?”

“I haven’t sculpted anything in months.”

She started to ask how he decided to make the transition from sculptor to life artist, but Cal continued.

“I took this notion a few months ago to spend some time on a motorcycle, so I flew down to Johannesburg, South Africa and bought a bike. I started along the coast, then turned north. I hugged the coast through Nambia, Angola, the Congos, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea.”

“That’s awesome. You should write a book about that.”

“I did.”

“How come I’ve never heard of it?”

“Because I’m not famous.”

Awkward moment, she didn’t know how to respond. She hoped Brett could save her, but he was still several places back in line. What to say?

“Now that you’re back, do you think you’ll start sculpting again?”

He scratched his beard. “Either that or something else. I don’t know. I felt passionate about writing that book when I got back, but after not having to be anywhere or do anything for months, it’s hard to go back to work just to support myself.”

“But you will.”

“I have to, when the savings run out.”

“Why not sculpt? Wouldn’t that be better than any other job?”

“I’m good at sculpting, but don’t want to dump a bunch of uninspired crap into the world. What if people liked it? Others might copy it, and the shit would just multiply exponentially. Better to do nothing than practice with negligence.”

Olivia didn’t even know what to say after all that, but luckily Brett returned with their beers. Were all artists so flighty? Hadn’t Brett stopped painting for periods before and traveled around, exploring exotic corners of the world? What did Brett or Cal get out of their travels? Were artists naturally prone to depressive lulls? If so, what did that do to a person? It was hard imagining, having come up all these years in a business environment, approaching every day in a work-woman-like manner, fighting fatigue, defending your work to your boss, powering through emotional troughs. She wanted the freedom of rejecting the materialistic world, but could she sleep

at night if she didn’t know how she was going to care for herself? How could she live without health insurance, without savings? Maybe she wasn’t built for the artist’s life.

Cal wandered off, and Brett took Olivia by the hand, leading her through the crowd towards the front of the stage. In between sets, people were variously standing, laying on blankets, some had their dogs, others had their infants, people of every race, people from all walks of life. Music the great bonding agent.

“What did you think of Cal?” Brett asked, once no one stood between them and the stage.

“He was really interesting. Let me ask you a question, though. How does someone like Cal who doesn’t have a job and doesn’t want a job not have all the anxiety in the world?”

Brett sipped on his beer, smiled and provided the most obvious answer in the world:

“Faith.”

Chapter 27

“These paintings, my God, Brett, they’re fabulous!” Salina exclaimed, holding one of the smaller pieces to the light in her high-rise office. Her digs were so opulent, even the light from outside was stylish. Brett twisted a friendship bracelet around his wrist, a gift Olivia had bought him a few days ago at the watermelon festival. In return, he bought her a crown of wild flowers. They’d drank milkshakes until they both got belly aches and snuggled at his apartment, watching shows on Netflix until the single-digit hours of night.

“Six, seven, eight paintings. Eight paintings! How long did you spend on these? You must not be sleeping.”

“Just a few days. The images have really been coming to me. I think it’s because I’ve gotten on a pretty good schedule.”

Salina looked at him behind her spaceship-grade-aluminum reading glasses, the kind you’d more likely expect to find on a rocket scientist studying the arch of parabolas on a green chalk board in an office overlooking live launch pads. “I’ve represented a lot of artists the last seven years, and none of them produce work like this because they’re on a pretty good schedule. I mean, this stuff looks like you must have swallowed a bag of Tinkerbell’s magic fairy dust. I mean, this one with the ant triumphantly carrying the bread crust back to the hill with all the other ants glowing with such admiration, why, it’s just phenomenal. I have no idea where you get these perspectives.”

“National Geographic.”

“But still, the idea to paint this is ingenious. No one’s doing anything like this in the market, but it speaks with its own authority. I’ll have a hard time sending these to the Alexandria collector, when I know they could fetch so much more hanging in a gallery. How you’ve anthropomorphized the ant, turned a colony underfoot into an empire, a bread crumb into the sustenance of a civilization. I’m--,” Salina stopped, patting her heart.

Brett had been half listening as he dreamt of being back in bed with Olivia, tucked under his arm, watching Before Sunrise in his bed, reading Style Weekly, eating fresh paw paws with the juice running down his chin and dripping onto into her hair, stealing glimpses of her reading a short story from the latest edition of the Virginia Quarterly Review. Salina’s silence brought him back.

“Yes? You were saying something?”

“I’m moved,” Salina said. She could have this harsh way of holding a painting, like it was a tool of commerce, like a construction worker wielding a sledgehammer before he ripped through drywall, but in this instance, she held the painting with the light touch one holds a newborn. “I want to buy this one for myself.”

Brett laughed. “My broker is getting into dealing?”

“No, I want it for my dining room.”

“Next to the Soto?”

“Where the Soto is hanging.”

“Really?” Brett said.

“Quit wasting your time here,” Salina said, waving him away. “Go back to your studio. Go back to whatever it was you were doing, and do it just like this.”

“You think the Alexandria buyer will be pleased?”

“Pleased? Try blown away. I wish I’d studied literature so I could describe it. Speaking of elegant description, I can’t believe I almost forgot. Pinstead finished his review. It’s going to be published in the New York Times.”

“Almost forgot?” he asked.

He felt like he’d been drilled by an Apache arrow on the unsettled plains in 1850, a hundred miles from the nearest civilization, predating modern medicine by a hundred years, holding his guts in, watching his life drip through hands, war whoops growing louder, tomahawks intended for his scalp being raised. Almost forgot.

“Well what does it say? Do you know what it says?”

Salina handed him a tan folder. Thirty stories below, the James River rolled past, unaware that Brett’s fate was already sealed. Brett held the folder in his hand, its contents for just another moment unknown, his afternoon froze: time stopped, shattered, and was swept away by the occasion. Unread it was powerless, but there were only a few lunches between now and when this appraisal would be posted on one of the most important bulletin boards in the art world. Brett opened the folder and read:

Authenticity in America

Inspired by cave paintings and indigenous art, Mr. Bale paints in urbanity’s closest approximation to a cavern — an otherwise empty, desolate warehouse, lit only by torch and the sun as it beams down through giant skylights dizzyingly high above, where in the center of his space is the well-spring of the most authentic art of the generation. If the WWII generation was Lost, this Beacon of hope is an oil-based testament to his generation being Found. Bale possesses an acute sensitivity to the vibrating hum of the planet, and conveys his generation in tune not only with art but also with finance, medicine, technology, servanthood— and these in touch with each other. Although many years need pass before we’ll have the benefit of posterity’s reflection on Mr. Bale’s work, his vivid portrayals of the organic universe give us the courage to pause, discard our to-do lists, breathe, and appreciate the beauty of creation that inhabits the otherwise most insignificant nonentity in our surrounding. Mr. Bale’s achievement is more than the courage of content or the sexiness of style; he has contributed an as yet uncategorized new dimension to his medium, which for lack of a more expansive vocabulary, I shall describe as the medium of desire.

— A.P.

“Not bad, huh?” Salina asked. “A little mushy and esoteric, and I regret he didn’t compare you to a well-known master but--”

“Not bad?” Brett asked. His inflection changed to declarative. “Not bad. How many more paintings do I owe the Alexandria contract? How much time do I have?”

“You owe the Alexandria collector four more, but I suspect he’ll give you one more extension on the strength of these. I actually pushed back on a contract from Charlottesville earlier this week for twenty new pieces, but I’m going to get on the phone as soon as you leave and tell them to send over the paperwork. I might even send them one of these for goodwill.” She squealed and kicked her feet and clapped. She returned to her desk, shuffling papers and clicking on her mouse. Then she corrected her slouchy posture, peering over top of her computer monitor. “Get out of here and paint! Shoo! Shoo!”

Chapter 28

“I’m going to run home,” Olivia said. Brett sat at a small desk by the large bay window in his apartment, sketching with charcoal, wearing only white overalls, his chest hairs curling over the top of the bib.

“Why? Stay here. We’ll get lunch.”

“I need clean clothes.”

“You look great.”

“I’ve worn these jeans four days in a row. That doesn’t work in this heat.”

“So just don’t wear pants.”

“Nice try.”

“Hurry back?”

“Of course,” she said. She leaned over his shoulder, pecking him on the lips. She couldn’t help but giggle at his silliness, his overalls evoking the image of a roman toga. The image stayed with her while she drove to her parents’ house.

“Well, hello there,” Kelly said, under a thick layer of sarcasm. Despite the early

August heat, Kelly wore a cotton cardigan and was otherwise snuggled up on a leather armchair, surrounded by a tower of books and tissues, as if hunkered in for the coldest days of winter. So innocent, she looked.

“Hey, Kelly.”

“Where have you been?”

“Just out.”

“For four days?”

“I answered your texts.”

“You didn’t say where you were?”

Her mother suspected her of sleeping around, no doubt, but she kept up the mystery. Nosy people needed hobbies. Brett made her too happy to care what her mother thought, or what anyone thought. Besides, she was sleeping around, and she wasn’t about to discuss it with her mother. Avoidance was really the only tool in her kit.

“I was staying at a friend’s house. I told you that. I just need to get out of the house sometimes. I’m 26 years old. Sometimes I just need to be with my own kind.”

“If you’ve been at a friend’s house, then why won’t you tell me which friend?”

“You weren’t so nosy when I lived in New York.”

“You weren’t living under my roof.”

“It’s not like I was a different person. Nope. Still just the same old Olivia. Living life.”

Olivia made a move for the stairs.

“Are you fucking that artist?”

Olivia stopped dead in her tracks. Oh no, she didn’t. Her mother never, ever, used profanity. She was a strict Catholic, with the passion of a zealot and the rigor of an academic, and she’d always conducted herself as if sins, once committed, could never be forgiven.

“No,” Olivia said, not only shocked but annoyed by the question and by her mother’s attempts at degrading her. A small part of her, the good Catholic girl, regretted not telling the truth. Why hadn’t she just told her mother she was falling in love? After all, there was nothing wrong with spending all your time with and giving yourself to someone you were passionate about, but she’d already taken a position. She decided to stick with it.

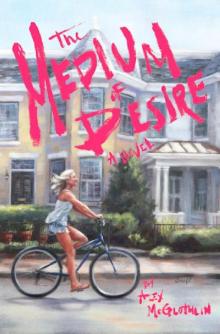

The Medium of Desire

The Medium of Desire