- Home

- Alex McGlothlin

The Medium of Desire Page 20

The Medium of Desire Read online

Page 20

“What the hell, girl?” a grizzly bearded man yelled from his jacked-up, diesel fueled truck.

“Sorry,” she said with a wave, hurrying across the street into Cordwainer.

The store seemed unusually busy for 2 p.m. on a week day. The walls were lined, floor-to-ceiling, with loafers, boots, basketball shoes, and fine footwear of various makes and models. College guys rummaged through a bin of vintage sneakers, filtering through Reeboks and Nikes, paying for their merchandise, making small talk with clerks.

Olivia eyeballed all the shoes variously displayed in the store until her eyes fell on a pair of calfskin Salvatore Ferragamo loafers.

“You like those?” asked a sales associate.

“I do like those.”

“They aren’t making that style any longer. They’re a collector’s item.”

“What sizes do you have?”

“We’ve got size 10. That’s the only pair.”

“That’s the size I need.”

“Your foot looks a little smaller than that.”

“They’re for my Dad.”

“That’s a nice gift for Dad,” the salesman said, leading her across the sales floor. He retrieved a small stepladder, unlocked and lifted the glass lid, forcing the Ferragamos in her arms.

Although there was only one other customer in line at the cash register, he was taking forever, making annoying small talk with the cashier, asking where they got their merchandise, how they priced their merchandise, what their mark-ups were. The cashier acted like he didn’t know because it wasn’t his job, but Olivia suspected he might have known more than he let on. The more the cashier apologized for not knowing, the more feverishly the customer reformulated his question. She had visions of Brett holding Carol’s hand, the two laughing, skipping down the street, Carol probably talking shit about her. She started to worry she wouldn’t have enough time to do what she needed to get done today, fully-cognizant she didn’t really have to do anything. She had plenty to do with moving to San Francisco, but since she hadn’t started the process, she wasn’t really getting behind. Maybe she hadn’t made up her mind. Sweat gathered on her palms. Were these guys ever going to finish this transaction? Her heart beat in her rib cage like a feral cat punching to get out of a trashcan. Stay calm, Olivia.

The conversation ahead of her finally concluded, and she pushed the shoes across the counter, frantically searching for her credit card, which was not where she normally kept it.

“These are great loafers,” the cashier said, packing them in a cedar shoebox. “I would have bought them myself if they’d been my size.” He was well under six feet tall and she wasn’t so sure the shoes wouldn’t fit him. She wondered why she even cared why he hadn’t bought the shoes and surmised there must have been at least a half dozen possible good explanations. Surrounded by all the shoes, she imagined she was in a CEO’s walk-in closet, unprepared before the big negotiation, with all the attendant dread, uncertainty and irrational, but very real fear of mockery.

“Cash or credit?” the cashier asked. She realized she’d been staring at him dumbly. She broke open her wallet, exposing her filed away dollars.

“How much are they?”

“Four-fifty.”

She didn’t have to count because she knew she wasn’t carrying around that much cash. “I can’t find my credit card.”

“Okay. No problem. Would you like me to put these on hold?”

Exhaling a metaphysically-infused sigh, she hated to ask them to keep their merchandise off the rack while she struggled to function as a basic American consumer. She reinitiated her search for the credit card, with a renewed vigor, and finally found it lodged behind a credit-card shaped package of chewing gum. She gave him the damn thing. He asked her to sign the receipt; she scrawled her name illegibly. Pleasantries were exchanged. With purchase underarm, she marched out of the store. Her car was parked down the street to the right, but she turned left, walking at a quick pace. She vacillated between breaking into a sob or a hysterical laughter. She conducted herself down the street to Saison Market, all limbs under manual control to prevent the spasms she feared were inevitable if each movement were not choreographed, lifted a single-serving bottle of wine from the refrigerated shelf, paid, and quickly found a small table facing a large map of Virginia. She popped the cork and didn’t bother with the formality of pouring a glass. She tried to structure her wild thoughts, trying to convince herself she had an average degree of emotional acuity.

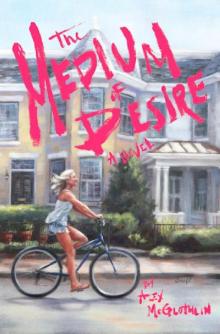

She had left New York to look for a happier situation. Richmond with her parents was supposed to be as good a place as any to endure what she expected to be a long, rocky transition period. Now she was sitting in a small market drinking wine in the afternoon alone, rethinking her original design. She stared up at the large map of Virginia on the wall, the state’s diverse topography illuminated by the cartographer’s artful shading, stretching from ocean across farmlands to coalfields. What strange negotiations were conducted to arrive at the unintelligible shape of Virginia? The Civil War, for one. She traced the partial demarcation of West Virginia’s unattributed boundaries of defiance on the map. She closed her eyes and dreamed of what Brett thought before he put brush to canvas, speculating about the countless images that must pass through his mind every day, whole worlds flickering through that theater of a mind, so many flares he never got the chance to sketch, extinguishing forgotten. She closed her eyes and saw the painting he had done of her, riding the loaner bike through the Fan, a romantic and honest painting. Maybe if she had nothing else, maybe if she had that painting, if she had just that little piece of their time together, she could move on with her life. Maybe the painting was all she had wanted in the first place; the revelation of self-discovery it provoked. She laughed, drawing the attention of others around her. If only she could believe such a delusion.

Chapter 35

Salina’s house was a sprawling two-story brick Georgian with an eccentric thatched roof in one of the city’s thickest enclaves of wealth, a place where Mercedes lined the streets because garages and driveways were reserved for finer cars. The pale glow of the 24-hour street lights was carefully engineered to be ever-so soft, so not to disturb softly-lived lives. Brett never got over Salina’s house and the impression it left of insatiable greed. Having made his objections known, she rarely invited him to her junior estate, but in contrast to custom, she had rather forcefully insisted he meet her here at 11:15 a.m. Such a business time to meet. Like, what did she have going on those first fifteen minutes of the eleven o’clock hour? It sucked to go all the way out there, and she knew that, but she hadn’t given a damn when she requested his presence for an urgent meeting. He was already broke, what else could be falling apart? Maybe he was being cut from her roster.

His Uber stopped in front of the well-manicured lawn, the entry adorned with peacock statuettes. He might have thought someone was playing a joke on the aesthetic savant, but the polychromatic-tailed geese were a staple, molded out of this high-quality iron. Salina threw open the front door.

“You’re late,” she said.

He sighed. He was reminded of grade school when the loud speaker compelled him to report to the principal’s office.

“I’ve got news for you, Brett. Come inside,” she said with a wave, and without waiting, disappeared into the interior recesses of the monolith.

Brett passed through the glass storm door, it slamming behind him. “Salina?” The excitement in her voice upshifted the beat of his heart.

“Back here,” she called.

He walked through the foyer, encircled by a spiral staircase, his attention drawn to the light beaming through a vaulted oculus. The room was scented with gardenias and covered in everything from a Lichtenstein print to her prized surrealist piece by a Max Ernst disciple. There were paintings by his contemporaries representing the mind’s chaos in paint splatters, reminders of the greatest wonder and most incontrovertible piece of evidence, that anything exists at all. He passed through the fo

yer into a colossal, open room that featured the kitchen, dining room and living room. Two large, French doors flared open and beckoned him outside to the pool deck. He reflexively shielded his eyes when he stepped into the sun.

“Brett, over here,” Salina said, waving with a dainty flourish. He peered through squinted eyes to see her seated at a wrought iron table, seated underneath the shade of a large umbrella. In front of her was a tray decked with half a sandwich, two martini glasses, a sweaty martini shaker, and a thin stack of papers, crisp and stapled.

Brett sat, slumping in the chair. He didn’t know where this was going, and he didn’t like business types, even his Salina, jerking him around. Come to think of it, he didn’t like anyone jerking him around.

Shaking the martini shaker, Salina filled an empty glass, and pushed it hap-hazardously across the table to Brett, some of its contents sloshing on his leg. If the one person he was beholden to for his income wanted to share a liquor drink before noon, well then, drinking was his business. She topped off her drink, and they clinked glasses.

“What’s the occasion?” Brett asked, shuddering at taste of the gin.

“The occasion is the rise of Brett Bale.” She straightened her thin stack of papers before handing them to Brett. The top center of the first page read:

Agreement

for

Presentation and Consignment of Art

“What’s this?” Brett asked.

“That’s your ticket to show at one of the most coveted art openings in the Western World. Niles Gergen and Wilma Latrob are already signed on. They were looking for the third artist to fill the final slot on the roster, which by the way is in New York, and after Pinstead’s article, the first person they requested was you.”

Brett didn’t know what to say. It sounded like a positive development, but he had no interest in going to New York. Couldn’t she just sell his art without him having to hit the sales path?

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t know? Don’t know? This is the type of show that makes an artist’s legacy, even without the showing, the association alone is invaluable. I can’t just place you in an event like this. It takes magic to get an opportunity like this. This show has international implications. They’ll expect you to deliver your best. It will take tremendous discipline to produce quality pieces for a show of this caliber. It’s soon, too, in three months.”

“But New York?”

“The last time they did this show was four years ago, and the lowest sales price for any piece was $50,000.”

Fifty thousand? Could that be real? If he could turn out 20 pieces for the event, that would be a million dollars. New York wasn’t that damn far way. Even if the trip threw him in a rut, the savings he’d build would provide him ample time to find a way out.

“I could make a million dollars?”

“Look, Brett, I have total faith in you. Just don’t go and get messed up with some crazy chick for the next few months. Consider taking a break from dating altogether. It wouldn’t kill you. Shit, I’d take a break from anything for a chance at million bucks. Shit, I will take a break from anything, in a show of solidarity, to get my commission on your million bucks. What do you say?”

“You’re implying I’m emotionally unstable. How do you get clients when you’re such a goddam typecaster?”

“I produce results.”

Chapter 36

Curling iron hot and makeup cases open, Olivia spent nearly two hours getting ready for the little dinner party she was hosting for her father’s 52nd birthday. She filed her nails and gave them a fresh coat of polish. She let her hair air dry, blew it out for ferocity, and curled it for the first time in years. The party was the first excuse she’d had to get prettied up since she had had her falling out with Brett. Though objectifying, getting pretty was empowering. Why not lure them in with her looks, and take them down with her wit? She’d never had a problem getting what she wanted. And therein lied her problem: since she left New York, she hadn’t been able to figure out what she wanted.

Without warning, her enthusiasm stalled. She could fake confidence with some drawn on makeup, but she couldn’t counterfeit craving. Paralyzed between two alternatives, at a crossroads between art in Richmond and finance in San Francisco, she burned for mutually exclusive lives, and she increasingly felt like she didn’t want anything at all. There was no tip in the scales, no impetuous for her to choose one life over another.

She heard shouting from downstairs, thinking at first that it was her parents trying to communicate from opposite sides of the house, but when shrill profanity filled their voices, she left the vanity to go and see what was the matter.

She descended the stairs just in time to see her mother march out the front door, climb into her car, reverse out of the driveway and speed away.

Leaning against the mantle, her father had a stoic air about him. He caressed his jaw with the backside of his hand. He pumped his foot on the ground, his breathing somewhat erratic.

“Where’s she going?” Olivia asked.

“Your mother’s pissed.”

“Why? It’s your birthday.”

“You really want to know?”

“I don’t know. How bad is it?” Olivia asked. “You’re not cheating on her, are you?”

“I lied to her.”

“Oh god. You’re a skank.”

“I didn’t cheat on her. She caught me smoking.”

“Smoking? Smoking? Who the hell cares about smoking with everything else going to hell?”

“I promised her I would quit, and I did. For years. But sometime after you left for college, I started sneaking an occasional cig, and I guess those occasions became habitual. She’s not so mad that I’m smoking as she is that I kept it from her. I just didn’t want her to worry.”

That was reasonable. It also sounded a hell of a lot like a rationalization for Dad lying to Mom, but it was Dad’s birthday, and Kelly shouldn’t be misbehaving on Dad’s special day.

“Where did she go?”

“She didn’t say. It’s probably best she blows off some steam.”

“That’s true,” Olivia said. “Say, Dad, what have you been doing lately? I mean, besides sneaking out for cigs? I don’t feel like you’ve been around much.”

“I’ve been working. At the office tinkering with lesson plans. Staying caught up on the literature. Nothing too out of the ordinary. How about you? What’s been up with you?”

Of course, her virtuous father wasn’t cheating on Kelly. With the way Kelly had been acting lately, why would anyone want to hang out with her? Her thoughts shifted from her parents’ relationship to her relationship with Brett. She wanted to cry but held it, fought it back.

“Honey, are you alright?” Dad asked. He moved from the mantle to wrap an arm around his daughter, leading her to the couch. He’d only called her honey a handful of times in his life. “Have I missed something?”

“I don’t know. I’m just at such a crossroads,” Olivia said, choking a bit.

“Do you want to tell me about it?”

“It’s just, ever since college, I always thought I had such a clear picture of what I wanted and where I was headed in life. Maybe I still don’t fully understand what happened in New York. I mean I do, this peon stole my work, they were sexist, and I didn’t have any prospect of promotion. But I could have been smarter about my transition. I could have avoided having to come live with Mommy and Daddy for months on end.”

“We love having you.”

“I know, Dad. I just, I find myself questioning how motivated I am to go back into finance.”

He stroked the back of her head. “I’m sure you just feel that way because of this contract bullshit. Once you’re out of that agreement and you’re able to start working again, you’ll move to San Francisco and this momentary crisis will fade away. I mean, San Francisco.”

“I was let out of that agreement two weeks ago, and I haven’t even told you or Kelly, much less

made any effort to move. I haven’t even told the firm I’m free to work. It’s not because I don’t want to work.”

“Why do you think you’re less than eager to go?”

“I think, if I’m being honest, I enjoy being around here. I started taking those painting lessons, and it reminded me there’s more to life than the grind. More to life than accumulating money and a few nice things. There’s something special and romantic about life here, and I’m not ready to let it go.”

“Your mother might have mentioned there was a boy, too?”

“Yea.”

“The artist.”

“Yea.”

“He’s pretty special?”

“Yea.”

“Your mother doesn’t like the idea.”

“No.”

“Honey, can I give you some unsolicited advice?”

“Always.”

“You first got interested in finance because your mother pushed you. You decided to move to New York because your mother pushed you. Your mother wants what’s best for you, but she doesn’t know what’s best for you. You can’t follow a path just because your mother wished she had taken it herself. You have to make your own choices. Finance or art. Success or failure. Rich guy or the guy who makes you excited to get out of bed in the morning. These are important decisions, the most important, and you can’t let anyone make them for you, not even your mother.”

The Medium of Desire

The Medium of Desire