- Home

- Alex McGlothlin

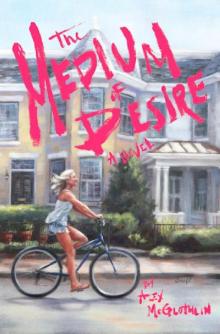

The Medium of Desire Page 6

The Medium of Desire Read online

Page 6

“Don’t be silly,” he said. He dropped the newspaper and flicked his cigarette into the void. “I’ve been expecting you. I was actually just cramming before we started your first lesson.”

“What do you have to cram for? Aren’t you a master?” She gestured quotation marks when she said ‘master.’

“It’s a field no man ever masters. And you’re my first student. I started thinking about it, and while I like studying this stuff, and I love painting, I don’t often have to put the technique, or for that matter the spirit, into words. I’ve been debating what to explore first.”

He sat up, stretched his arms to his sides, and hopped to his feet.

“I landed on discussing technique for the majority of the class,” Brett continued, “but I want to start with a word on the spirit. I don’t paint just to preserve a record of the past. I paint to stretch my capabilities, enrich my understanding, to reach a higher plain of self-realization. I don’t paint to produce. It’s just what I do. I paint because I have to.”

His passion was nice, even if he was being a bit basic and possibly even cliché, but it made him seem vulnerable and sensitive and these weren’t qualities she had expected from him when she met him at Max’s. Her first impression was that he was just a ruffian with a lucky brush and a bad boy streak, traits that had always grabbed her attention. But now she was seeing more.

“That said, I think before you can channel passion, you have to experience some pleasure in the effort, so it’s important you quickly get to a point where you can produce simple, competent paintings.”

“I told you I’ve painted before,” she said.

“I know. But you’ll have to be patient with me, since I’ve never taught before. I’m just trying to start at the beginning, so you get a solid foundation.”

She was still offended, but his genuineness took shock out of the blow. His nervousness was cute; she warmed to it. He was sweet in a way.

First, he introduced her to arranging paints on a palette, showed her how to mix colors without wasting or making too much of a mess. Then he gave her a clean brush and told her how to face the easel, with her feet sideways so she looked over her shoulder, knees bent in a warrior’s pose.

“We stalk images in pure imagination, hoping to capture emotion. You ask yourself: what stirs me? What is the nature of the intrigue? We capture those elements honestly without romanticizing them, and let them assemble themselves on the canvas as a testament to our inspiration, to a moment of heightened awareness.”

She began to dab the brush on the pallet and brush lines of a dusk orange sky, earthen brown landscape, a pink sun. It was looking good, and it felt amazing working the brush with a muse in her ear, inspiring each stroke of the brush, each stroke a step towards completion. She started to paint the yellow abode buildings she considered the focal point of her painting; however, the original form she needed to compose began to disintegrate into sketchy, childish, one-dimensional buildings. She had originally imagined painting people walking through the street, too, but people were much more difficult than buildings. Suddenly the entire endeavor seemed impossible. She handed the brush to Brett.

“What are you doing? You’re doing so well.”

“You’re patronizing. My buildings look like shit.”

He stepped in front of her and gazed hard at the painting. “They don’t look finished,” he said. “But that’s because your toolkit lacks perspective. It isn’t difficult to construct an object in the dimensions of its space, but it is something you have to learn. That’s the purpose of today though, right? To get a baseline reading, so we know what to work on going forward. Isn’t that what we’re doing here?”

“I guess so,” she said. She was surprised at how defeated she felt not being able to paint realistic looking buildings. Those squares she had drawn were sad. She took the brush from Brett, swished it in the can of paint thinner, wiped it on her towel, dabbed it in the desert earthen brown and started to smear out all the work she had done on the buildings. Brett snatched the brush from her hand.

“You can’t erase just because you think you failed. What other record of your progress will you have to study? You need this painting, that one-dimensional square box for our next lesson.”

“Next lesson. Are you saying we’re finished? But we just got started,” she said.

“I don’t keep track of time. I just do things until it’s time to do something else.”

“I guess, then, I should ask you what I owe you for the lesson?” she asked, slipping her hand in her front pocket.

“I’m not doing this for money.”

“Then what are you getting out of it?”

“I don’t know. Salina wants me to take on apprentices, so I can turn out more paintings. Apprentices need to be trained.”

Apprentice? She was simultaneously offended and flattered. She started to either inquire what was required of an apprentice or object to the classification, but decided to hold her tongue. She didn’t want to ruin the good vibe she felt in the moment.

He wiped the paint from his hands and dropped the rag on a table that housed an array of interesting things: a skateboard, a whale’s tooth, a civil war musket, beautifully finished paintings lying spread across the table, lying next to dirty rags and stacks of yellowed magazines with the pages curled, piles of books on art, classic literature, books filled with pictures of paintings, an iPad, a bronze statuette covered in Hindi script that resembled a weaponized baby’s rattler, and other things. If only she cared to continue looking. Two bikes leaned against the table, one a matte red mountain bike and the other a blue beach cruiser with a metal basket by the rear wheel.

“Who’s bike?” Olivia asked. She heard her own jealousy the moment the question rolled off her lips.

“That’s my sister’s,” Brett said.

That’s a relief.

“What’s she like?”

“She’s an international flight attendant, so I don’t get to see her often. But she’s wonderful.”

“I see,” Olivia said.

“What brought you to Richmond?”

“My parents moved here a few years ago to teach at University of Richmond. I thought I’d come spend some time with them while I waited on my do-not-compete clause to expire.”

“That’s interesting. What’s that all about?” Brett asked.

“When I signed the contract for my last job, there was a provision that if I quit, I couldn’t work for another hedge fund for six months.”

“That’s wild,” Brett said. He rocked the beach cruiser back and forth, pressed his weight on the handlebars as if examining something, maybe to test the pressure in the tires. “Let’s go for a ride.”

“What about our lesson?”

“I’ve only got so much stamina for teaching. Besides, you need to let it all soak in,” he said. He wheeled his sister’s bike in front of her.

It was the right size for her. She threw her leg over the seat and when she looked up, Brett was already riding towards an opening garage door, a bridge of light opening in the void. As she approached the exit, she noticed the walls around the door were covered in an extraordinarily ornate graffiti of overall-clad hillbillies standing beside moonshine stills, goats grazing on steep hills, marijuana fields shamelessly cultivated over and above the ridgelines.

When she rode out on to the street, Brett was already half a block ahead of her. He looked over his shoulder, waving to her, and she peddled furiously to catch up.

“Are we going to a gallery?” She asked.

“No,” he yelled over his shoulder.

“Then where?”

“I haven’t figured that out yet.”

They crossed Boulevard and turned onto Monument, where there were gargantuan statues of confederate generals from the Civil War, the avenue lined by mammoth town houses, if you could call them that, mansions in the townhouse style, with a big green landscaped field of trees dividing the opposite lanes of traffic. Despite the glo

rification of the south’s dark institution, the neighborhood was authentic in an unfamiliar, unself-conscious way. They rode past the emptied summer-session streets of VCU and deep into the heart of the financial district with its high-rise buildings.

Brett rode up alongside Olivia and asked: “Did you notice how we just rode into an aesthetic void?”

She hadn’t.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean like how we just rode from this charming vegetated area with thought for architecture and living, and into this congregation of steel, glass and cement sun blotters filled with copy machines and automatons.”

Olivia always liked being in the city. It’s like, where you’re supposed to want to live and work. But she tried to see it from Brett’s perspective. Not too many paint-covered artists wandering the streets down here.

She looked at him, and was pleased to exchange a few more gazes with him than mere friendship permitted. They turned sharply downhill and did a lap around Brown’s Isle, a cute little river island just beyond the shadow of the city skyline.

“Do you feel like you can breathe better down here? I can,” Brett said. She followed him back into the Fan to a little café called Lamplighter, where they ordered Mexi Cokes and sat on a picnic table in the sun.

“And that’s Richmond. We basically just took a bike ride through the past, the Fan, the present, the financial district, and the future, Lamplighter,” Brett said.

“And where is the future leading us?”

“They say history goes through cycles, and we’ll probably continue to go through cycles, but there’s evolution, too. Richmond’s preserved the past while clearing a way for the future, and it’s made for an eclectic, rich moment.”

“But is it original?”

Brett removed a packet of cigarettes from his pocket, tapped one out, lit it and took a deep drag. He stared at the oceanic blue sky. Sweat glistened on his beard.

“Originality is such a gooey subject. Is it original to appreciate all that’s past? Is it unique?”

“I mean, if you’re painting a painting in the strictly baroque style then it isn’t original, it’s merely reapplying a centuries old technique.”

“Really? Isn’t it original to stop and appreciate all that has come before if the act of stopping and appreciating all that has come before has never been done?”

“I think the definition of unoriginal is doing something that’s been done before.”

“You raise a good point. Think of it this way though. Assume I paint with a baroque style. Is my baroque painting of a guy skateboarding to class while checking his iWatch going to resemble anything that was done in the 17th century?”

“No. I mean, your subject selection combined with the style are going to be unique, but the style alone isn’t unique and neither is the subject.”

“But it only takes combining two things that have never been combined before to make something unique.”

“Is that your recipe?” she asked, regretting her words immediately. Why was she being so harsh when he was being so nice? Studying a bird pecking at a discarded aluminum foil sandwich wrapper, he didn’t react. “I get it though. You’re trying to get through to me,” she said. She had no problem being deferential at work, but it was hard for her to be so humble in a social setting. Was this a social setting? Was she being disingenuous by letting him believe she was aspiring to be his apprentice when she had plans to leave for San Francisco in less than six months?

“I’m probably coming off as condescending, like I said earlier, but I want to make sure we don’t gloss over anything important. Getting started is always the hardest part.”

“What’s the second hardest part?” she asked.

“I’m being misleading when I say hardest part. I should say the part that requires the most focus.”

“So, you don’t differentiate between starting and finishing?”

“I differentiate between the stages a great deal. The amount of effort involved in each of them is the same, it’s the type of effort that varies.”

She thought about that for a moment. He was right, of course. She wanted to take notes on what he was saying, but she was too proud to do that in front of him. She’d have to remember to write it down later.

“So you leave what I assume is a busy job in New York, and you come straight home to mom and dad. No other places to see, people to visit?”

His insinuation stung, but she told herself it was unintended.

“I don’t know. I guess most of my friends are either in New York or Ann Arbor. I lived in New York, and I get back to Ann Arbor a few times a year,” she said. “Where do you visit?”

“Oh me? I’m from Richmond, so pretty much everyone I know lives around here.”

“You didn’t leave to go to school?”

“I went to VCU.”

“Have you ever gotten out of Richmond?”

“I did once. After I graduated VCU, my sister is a stewardess like I said, so I can fly on her buddy pass for a fraction of what a regular plane ticket costs. I caught up with Belinda for her furlough in Hamburg, but I met some people and when she went back to work I flew with them to Rome. I spent about a week there, all cliché riding around on a scooter, stopping for pizza in between touring ancient ruins. I was about to come home, when Salina called to tell me some of my paintings had sold well, so I went to Paris. I was in Paris for a month before I took the train through Spain and eventually down into Morocco, and then I made my way along the west coast of Africa until I landed in Ethiopia. I was in Ethiopia for a few months until I doubled back to Spain. The whole thing ended up being like a year.”

“Wow. And you were painting the whole time you were gone?”

“I didn’t paint a single brush stroke the entire time.”

“What did you do?”

“I toured around. Visited museums. Talked to people. Read books.”

“What did you read books on? Art? Philosophy?”

“Just whatever books in English I could find.”

She couldn’t contain her smiling at the thought of just traveling freely, feeling what she had felt when she skipped work with Cleo to wander around Greenwich Village, but feeling it for an entire year. The variety of experiences she would have, the beautiful things in all shapes and forms she would see, the interesting stories she would hear, the divine cuisines she’d sample. The idea of the experiences summed to a whole greater than their parts. It was an experience she could throw herself behind, especially now, while she had the time to do it. Of course, she would never dream of going on such an adventure alone. She needed someone to travel with. She wondered what he was doing for the next few months.

“I’d like to travel like that. Maybe you’d take some time off to show me some of your European haunts.”

He snickered.

“What? You’d hold out on me?”

“I don’t travel anymore.”

“What do you mean you don’t travel?”

“I mean I don’t leave Richmond for anything.”

“Why?”

“I’ve seen what’s out there, and I’ve seen enough. I don’t have any family anywhere else except Belinda, who’s impossible to track down, so travel’s just transit. I live in a studio apartment and ride a bicycle.”

“Why not go for just like, a month?”

“I don’t have patience for decadence.”

“But you enjoyed your big trip?”

“I just don’t travel anymore, ok?” A pained look overcame him and he quit making regular eye contact and his body language said more than enough to suggest she should change the subject, at least for now.

“What do you think about painting soup cans?” she asked.

He scratched his wrist where most people wore a watch. “My thoughts on Warhol are a little complex for today,” he said. He took the last drink of his Coke. “Should we go?”

She nodded.

They mounted their bikes and rode down Floyd Avenu

e, beside each other, the sun flickering through the leaves as they exchanged glances. He lifted a leg over his seat and rode side-saddle, and she lifted her legs and rested them on the crossbar. They took a few more winding turns before arriving at the studio.

“What do you have to do now?” she asked, biting her lip as she leaned the bike next to the table of interesting things. She wanted him to ask her to stay, but for some reason she knew that wasn’t going to happen. Their conversation had turned a little awkward towards the end to just rush into a sexual frenzy. Sexual frenzy? Who the hell was she? She should have just asked him to show her some cool bars around the Fan or something, but to make that suggestion would have risked showing her hand.

“I have another appointment,” he said.

“Okay, cool.”

“Set up another lesson as soon as you’re free,” he said. They walked through the heavy steel door that had given her so much trouble earlier, he locked up and peddled off, giving her a big wave as he sped along the stark industrial streets.

Chapter 8

Whistling and calling the dog’s name, Sioux was nowhere to be found when Brett arrived at Comida del Sol, and neither was Paco’s skateboard. They hadn’t discussed meeting up, so he shouldn’t have felt disappointed. Brett was eager to talk, so he pushed on, peddling towards Paco’s house in Jackson Ward, where he lived with his mom. Brett careened through the city streets, selecting alleyways over the boulevards, peering over fences into other people’s backyards, always alert for the next visual that had that Kerouacian it. Turning onto a particularly sloppy side street, some people thought their sidewalk was an acceptable place to dump sofas, mattresses, an old refrigerator, bags of raccoon-pilfered trash. How could people just toss stuff right outside their homes and expect it to vanish? Someone must eventually cart it away, otherwise the whole city would be a dump. He laughed at the rebuff he’d get from art circles for calling trash dirty, or expecting people to spend, better yet waste, precious time doing their own chores. He’d been called anti-contrarian, but he hated that label. He was really more post-contrarian, or contrarian as he saw fit. He did what he wanted without regards to other’s opinions.

The Medium of Desire

The Medium of Desire