- Home

- Alex McGlothlin

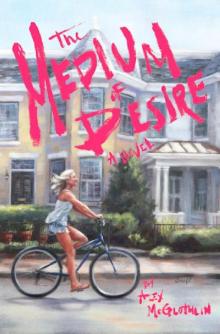

The Medium of Desire Page 7

The Medium of Desire Read online

Page 7

He arrived at Paco’s house, and being a friend of the family, dropped his bike on the front steps and walked inside without the formality of knocking. The house was plainly decorated but very clean, the only evidence of art a few family photographs and a painting of the Last Supper hanging over the mantle. Roman Catholic prayer candles lined otherwise empty bookshelves. A bronze cross held a central position on an accent table in the room’s natural focal point.

Brett whistled. “Paco.”

Paco answered from the backyard. Brett walked through the kitchen and let himself outside through a glass door. Paco sat on a lawn chair next to his 17-year-old brother Jesús. They giggled about something in Portuguese and drank beer. A tub of iced Stella Artois rested at foot.

“Sup man,” Paco said. He dipped a dripping wet beer out of the tub and tossed it to Brett, dampening Brett’s shirt.

“Big things.”

“Yea? You seem lit up,” Paco said.

“I hung out with this awesome girl earlier, Olivia. I spent like the whole day with her.”

“You’re finally on trigger again. Hit that?”

“Nah man. I’m teaching her how to paint. I actually feel maybe a little in love, but I’ve never had a student before. Is there an ethical issue with dating a student?”

“Dude. This isn’t high school. Do whatever you want.”

“Would I be taking advantage of her?”

“You’re not taking advantage of her if she likes you,” Paco said.

Brett looked for the bottle opener, but Jesús gestured for him to pop the top on the edge of the iron table.

“But I’m, like, in a position of power over her,” Brett said.

Paco spewed beer out his nose. “Bro, she’s had one art lesson. How old is this chick? Fourteen?”

“She’s like mid-twenties.”

“Why are you trying to talk yourself out of liking a girl you like?”

Formulated that way, Brett understood why. He didn’t want her disrupting his life. But if he never took the risk to get to know an awesome girl, then wasn’t he setting himself up to spend his life only hooking up with chicks he barely knew? And wasn’t it shallow to hook up with a girl just to stave off loneliness? Perhaps the quest was, how much interest did he have to have for his feelings to be deep? He’d first spotted Olivia for her looks. Had she really dazzled him with her personality today, or was he trying to rationalize his superficiality? He contemplated all this while Paco said things he did not hear. For the time being, he’d have to deal with unsettled feelings.

“Anything else going on? Or you just come over here for a pep talk?”

“Something sorta, but it’s kind of stupid.”

“Hit us gamer. We got nothing but time.”

“It’s work stuff.”

“We talk about work all the time. Say, you look kind of nervous. I didn’t think art was supposed to be stressful. I thought if you messed something up, you just smudged it out and started over?”

“Salina got me a meeting with this big shot art critic.”

“That sounds awesome.”

“In a way, it is. But the guy doesn’t rave about every artist he reviews. He’s destroyed people.”

“Then fuck that guy.”

“But he’s also made careers. If I want to take the leap from getting by to being a made man, this is it. But it’s such a fucking gamble. I don’t know what he’s going to write. He could end the market for my work.”

“So what you going to do?”

“I told Salina I’d meet him.”

“Atta boy,” Paco said, cheers to the sky. “It’s going to be awesome. I know Salina’s got your back.”

“Oh yea, speaking of Salina, I wanted to talk to you about the kebab stand.”

“What about it?” Paco said, readjusting his posture, crossing his legs and tugging an ankle towards his waist, the comfort he had previously enjoyed having vanished.

“You still interested?”

“Of course I’m still interested. Why? What’s up?”

“I got the seven grand you asked for,” Brett said.

“Shut the fuck up.”

“Swear it,” Brett said.

Paco leapt out of his lawn chair and lightly shoved Brett.

“Don’t fuck with me bro.”

“I’m not fucking with you. I talked to Salina about it today, and the money’s good. We’re going to do this thing.”

Paco hugged Brett then backed away, still clutching a handful of Brett’s shirt, like someone would grab you before punching you in the face. “You’re too much bro. Too much.”

“Man, I’m never enough.”

“So I take it you’re in? We’re going to do this thing?”

“How many times I got to say yes?”

“Just one or two more times,” Paco paused. “I finally get to quit my job.”

“Just like that?”

“The money’s good, right?”

“Absolutely,” Brett said.

“Then I’m quitting. This afternoon’ll be my last shift. I’m going to tell Jefe to go fuck himself.”

“I wouldn’t go burning bridges.”

“Yea, maybe you’re right. Maybe I’ll just politely resign.”

Chapter 9

Brett strained to suggest hair on the cephalothorax of a spider slicked wet, straight up, just behind its head and stoned eyes, with a great abdomen bulging towards the sky, all supported by its spindly legs. Behind it, a cave combusted into blue flames, separated by a vast desert of sand, with small arching blue-green waves crashing on the beach, and a green meteor shooting through a sky smeared with blazing white stars. Sand molecules leapt in the sky as the spider fled, away from its presumptive home, its next destination in the broad universe unknown.

A knock at the studio door startled Brett away from his painting, and he became cognizant of the passage of time. It must be Olivia, who was supposed to come seven hours after he had started painting that day.

He greeted her at the door, still possessed by the intense focus in which he had raptured through the entire morning and the meat of the afternoon. He showed her inside, and they walked over to his stations. She started arranging paint tubes around a pallet, selected a thick and thin brush, and looked to him for guidance.

“We’re going to work on technique today,” he said.

“What do you mean? Aren’t we going to paint?” Olivia asked.

“We’re going to talk about why we paint what we paint.”

Olivia’s eyes searched the studio wildly for a moment, as if she was looking for something, and when her eyes landed on his recently completed painting, she looked as though she had found it.

In a conventional sense, he hadn’t prepared for today’s lesson. He wasn’t sure how to prepare. Olivia had some understanding of form, but before she could develop the techniques she needed to midwife her visions onto the canvas, she needed to understand what her vision meant, why she had selected that vision, and distill that vision into its essence before she could transfer it to the medium.

“Why do we paint what we paint?” Brett asked. “We paint what we paint because it affects us. We paint something that moves us, that stirs our interest, whether it be a reaction of awe or disgust, whether it startles or inspires. We record emotion, so what we paint necessarily reflects our inner state in the moment of transference.”

“You want to talk about subject selection?”

“I want to talk about the relative value of things.”

“What was the relative value of my Mexican village in the desert?”

“You’re kind of skipping ahead,” he said.

“Did I select wrong?”

“You can’t select the wrong image because one subject isn’t superior to another, but what elements you choose to portray that image are objectively ascertainable.”

She paused and seemed to consider what he said.

“You mean like I should have painted the market, or had

a man riding a horse into the horizon in the center of the painting?”

“Not exactly. You stopped painting when you couldn’t paint the buildings.”

“I couldn’t paint the buildings because I don’t know how to paint perspective.”

“That’s true, but you can’t paint the perspective until you see the perspective.”

“How do I learn to see the perspective?”

“It’s a chicken and the egg sort of thing, isn’t it?”

“Can I find it by staring at the subject?”

“Not exactly. What you want to discern are the essential lines of your subject, then record the essential and omit the superfluous.”

“How does one distinguish between the essential and the superfluous?”

“It’s a matter of judgment.”

“How does one get judgment?”

“You don’t really get judgment, you just grow in it. You can definitely develop through trial and error, but some people start with a great deal more judgment than others, and some never develop any judgment despite a lifetime of trying.”

“Why do people fail to develop?”

“My classmates at VCU debated that fiercely.”

“What do you say?” Olivia asked.

“Why do people fail to develop? I think it’s usually a lack of will.”

They stood close while Olivia fondled the tools. He wondered if she was disappointed by his paint theory jibberish, or whether he was making a genuine impression on her. It was hard to know such things in an instant, and some lessons don’t take root until a great deal of time has passed. At least, that had been the case with much of his development.

Olivia lifted a blank canvas and situated it on an empty easel. She mixed some paint thinner in a bucket and placed it on a small table by her canvas. He stood, watching her, saying nothing. She mixed some colors on the palette, took the heavy brush and started drawing thick heavy lines of paint. She dabbed her brush in a sun-eruption orange paint and drew several heavy discordant lines, then washed her brush and interspersed her current work with strokes of alternating-current blue. When she dabbed the brush in a hog-pen brown, he stopped her.

“What are you doing?”

“I’m painting what I feel.”

He paused for a moment. He had lived by the credo of form his entire career. Abstract could be legitimate, but it frequently led to a dead end. The gulf between celebrated abstract expressionist and every fool with a paintbrush was simultaneously an untraversable chasm and a mere stone’s throw. Success in such an endeavor was uncertain at best. But to paint form was to seek an objective achievement, to create a praiseworthy image. But what did he give a damn about praise? Without praise, he wouldn’t be painting and biking around Richmond for a living, he’d likely be grinding out some entry-level office job performing menial, recursive tasks while watching his boss trade-up on increasingly expensive cars, feasting on the harvest of his labor.

“You can paint abstract if you want, but on your own time. When we’re together we’re going to focus on form.”

“Why form?”

“Because form is everything,” Brett said.

“That’s a bold statement.”

“The building we stand in is form, originally outlined in an architect’s blueprints, the cement floor we stand on was planned, materials were gathered, the cement was poured and smoothed over with a trowel. All for a specific purpose, to attain a desired effect. The world we live in wasn’t created by an undisciplined child aimlessly tossing his toys around a room.”

“What if I specifically made a series of brush strokes without an end result in mind, and when I’m done I know it’s because it’s how I feel?”

“You’d be rationalizing. You’d be projecting your feelings onto the painting once you’d arbitrarily splattered a bunch of lines up there, but you wouldn’t have actually achieved representing your emotion on the canvas.”

“So every abstract painter is a charlatan?”

“No. But how do you expect to paint the depth and perspective of raw emotion if you can’t even paint the side of a mud hut? Isn’t the latter much simpler, more tangible and accessible than the former?”

She seemed simultaneously hurt and appreciative of his criticism.

“How can I paint my emotion if not through abstraction?”

“You paint it through a conduit. If you’re happy, paint a little girl blowing bubbles with the summer sun bronzing her rosy cheeks.” She started to speak, but he continued. “You paint an old man at winter time waiting by the window, and you capture the look on his face when familiar headlights park in front of his house, piercing a veil of fluttering snowflakes. You paint a boy whispering into a girl’s ear in the library, and she’s laughing, and they’re young and have their whole futures ahead of them. They’re wealthier than anyone before them or who will come after them because they aren’t concerned with comparing their happiness to others because they’re in a vacuum, with no yardsticks to measure their relative degree of happiness.”

“So that’s how you’re able to focus long enough to understand the perspective of your subject.”

“What?” he asked.

“You become so infatuated with your subject that you stay at it until you’ve comprehended its totality, until you catch an edge so sharp it sparks.”

He didn’t respond. He didn’t like being analyzed, didn’t like it when he felt someone had a good read on him, even if it was appreciative. Too much appreciation could make him lazy, make him look to outside sources for guidance and energy, and he refused to be anyone other than a self-sufficient man. Rather than answer her, he changed the subject. He dragged a small table by her easel and put an apple on it.

“What?” Olivia asked.

“What do you mean, what?”

“You want me to just paint the apple?” Olivia asked.

“Not just the apple. Don’t just paint an apple. Paint the apple as if it is the whole world, as if your portrait of that apple is of global significance, as if the apple is home to the whole world’s population and collective history, culture and identity. Paint that apple like God gave it to you just a moment ago, and you want to remember not just how the apple looked, but how the apple that God gave you made you feel.”

She started over. He gave her a new, smaller canvas, and she began to paint the apple. It was an organic green apple, with a few blemishes and freckles but was otherwise ripe and perfectly edible. He was curious how she would represent it. Would she romanticize it, and make it monochromatic green, or would she exaggerate the blemishes to make the fruit look spoiled? She began logically by painting its circumference, then spent a significant amount of time on the stem. Lastly, she painted the blemishes, then painted over the blemishes thoroughly with green homogenizing paint, only to return and re-accentuate the freckles by stippling black and a warm brown. She worked to get the body right, then returned to stretch the details, the characteristics that made it unique, before considering the greater unity and redirecting her energy to making the image look like fruit. She painted without prompt, straining between commoditization and individuality. Signs of her former skill, atrophied under years of neglect, began to emerge.

Eventually the details she fretted over delved into such minutiae that he resigned to allow her to make her own progress. She had the project thoroughly under control and any critique he might have offered would have been unjustified. He had asked her to paint something simple with passion, and she had succeeded. She was beginning to understand that her feelings could live on the flesh of the apple.

Brett had a flash of euphoria at the thought of training someone with such native intelligence. She had a marvelous knack and a high ceiling, but she needed a tremendous amount of coaching to reach her peak. It was exhilarating to think of the payoff. More than painting a masterpiece, he had a vision of molding a master, and perhaps she would instruct apprentices of her own, and the legacy would stretch on indefinitely, creating beautifu

l works and reforming the minds of modern man. Olivia was more than a student. As brilliant as she clearly was, she had the raw potential to be the flashpoint of a revolution.

Brett reclined on his couch and smoked and watched Olivia paint. What had started as a simple exercise had developed into an important work for her, like a litigator with her moment before the Supreme Court, a smokejumper repelling into a forest ablaze, a birddog charging into the forest thicket following the recoil of his master’s shotgun. Towards the end, she had to be in the finishing stages, her strokes intensifying, dabbing just the right amount of paint onto that little brush before dotting freckles across the skin of the fruit, her brush kissing the canvas. He tried unsuccessfully to suppress a thought, that there was something sexy in watching her work. Maybe it was the sensual way she handled her tools and approached the canvas. He was so captivated by watching her work that he nearly didn’t notice when she had finished, paint splattered on her San Francisco Giants t-shirt, her hands covered in paint, her hair tight in a ponytail behind her head, her legs bare beneath the short length of her khaki shorts.

She sat with him on the couch, notably closer than usual. He checked to make sure there wasn’t a cigarette between his fingers and there wasn’t. She was breathing heavy and looking at him with an intense gaze, like she was still grasped by the passion, still seeing, even though her work was complete. She was seeing him now. She moved in a little closer, and though he leaned imperceptibly away, there was hardly any space to give. He couldn’t take advantage of her, he wouldn’t become one of those lazy, sleazy hacks who got his fill by tricking a steady stream of vulnerable girls into his studio and letting the studio do the rest. She was his student. He still had aspirations. He needed to protect his process, which did not include a girl meddling with his emotions.

The Medium of Desire

The Medium of Desire